1. Learn to distinguish risk from volatility

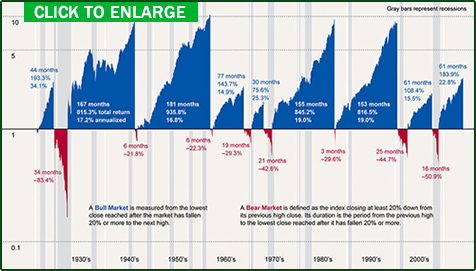

What do we do when the Big Bad Bear growls? Do nothing because risk, as we define it, is the possibility of permanent loss of capital – while volatility is the successive over-valuation and under-valuation that the market places on your fractional interests in a group of businesses. Each decline in broad market value has simply been a compressed pogo-stick waiting to bounce up to ever-greater heights.

Warren Buffett says it best: “Ben Graham, my friend and teacher, long ago described the mental attitude toward market fluctuations that I believe to be most conducive to investment success. He said that you should imagine market quotations as coming from a remarkably accommodating fellow named Mr. Market who is your partner in a private business.

Without fail, Mr. Market appears daily and names a price at which he will either buy your interest or sell you his. For, sad to say, the poor fellow has incurable emotional problems. At times he feels euphoric and can see only the favorable factors affecting the business. When in that mood, he names a very high buy-sell price because he fears that you will snap up his interest and rob him of imminent gains. At other times he is depressed and can see nothing but trouble ahead for both the business and the world.” Your job is to ignore him.

Look at the history of the Dow Jones or the S+P 500 indexes and see the remarkable rewards they delivered to patient investors who could withstand the volatility of markets. The long term rewards far exceeded bond returns and indeed the returns of almost every asset class – and are likely to do so well into the future. Buckle yourself in for a very bumpy ride to a glorious destination.

2. “Over the long term, equities have outperformed almost every other asset class.”

– Prof Jeremy Siegel – Wharton University

| “When I first arrived in this country in 1977, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was at around 850. It is now at almost 20 times that amount – and, including dividends, the Dow would amount to over 20,000.

During that period however, there were many catalclysic events that caused prices to collapse – but in time, each downdraft turned out to be the spring in the pogo stick.” Selwyn Gerber CPA RIA |

3. Most investors have horrible investment track records

Given what you just read, you probably won’t be surprised to learn that majority of investors significantly underperform the broad market indexes.

According to a study of investor returns conducted by Dalbar, a Boston-based analytics firm, the average equity fund investor has returned 5.02% a year since 1993. By contrast, the S&P 500 has returned an annual average of 9.22%.

As the study’s authors note (emphasis added):

We have learned that the greatest losses occur after a market decline. Investors tend to sell after experiencing a paper loss and start investing only after the markets have recovered their value. The devastating result of this behavior is participation in the downside while being out of the market during the rise.

The flow of money into and out of the stock market confirms this point.

According to data collected by the Investment Company Institute, over the past decade and a half, money gushed into stocks at the height of the market in 2000, 2004-06, and 2013. Meanwhile, the flows reversed course after stock prices touched bottom in 2002 and 2008.

4. Actively trading stocks is generally a losing proposition –

whereas holding quality equities for the long term has produced stellar returns.

We should take it as a hint that one of the seminal papers in the field of behavioral finance is titled “Trading Is Hazardous to Your Wealth.”

Beyond showing that trading stocks is a losing proposition, the authors demonstrate that it’s also a matter of degree. In other words, the typical investor’s returns decrease as his or her trading velocity increases.

As the authors explain:

Individual investors who hold common stocks directly pay a tremendous performance penalty for active trading. Of 66,465 households with accounts at a large discount broker during 1991 to 1996, those that trade most earn an annual return of 11.4%, while the market returns 17.9%.

One reason for this performance is our penchant for buying high and selling low. Another is that trading generates transaction costs in the form of commissions and taxes on realized gains.

Take this anecdote from Warren Buffett’s 2005 letter

to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway:

Long ago, Sir Isaac Newton gave us three laws of motion, which were the work of genius. But Sir Isaac’s talents didn’t extend to investing: He lost a bundle in the South Sea Bubble, explaining later, “I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men.”

If he had not been traumatized by this loss, Sir Isaac might well have gone on to discover the Fourth Law of Motion: For investors as a whole, returns decrease as motion increases .

5. Beware of experts (and the financial media)

If you watch CNBC or Bloomberg, you’ve no doubt come across countless experts who offer predictions about which way the market is headed. Unfortunately, the reality is that nobody knows, and it’s best to ignore anybody who claims to.

This is true of even the world’s brightest minds and best-known prognosticators:

- In 1929, Irving Fisher, by many accounts the “greatest economist the United States has ever produced,” claimed that the stock market had reached a “permanently high plateau.” This was promptly followed by the Crash of 1929.

- In 1979, a BusinessWeek cover story titled “The Death of Equities” concluded that, “[f]or better or for worse, the U.S. economy probably has to regard the death of equities as a near-permanent condition — reversible someday, but not soon.” The stock market soon set off on a 20-year bull market that culminated in the S&P 500’s 14-fold increase.

- In the mid-1990s, best-selling author Harry Dent Jr. predicted that the Dow was headed to 40,000. Nearly two decades later, it’s short of 17,000. And in the interim, it crashed twice. That hasn’t stopped Dent. His latest book, published earlier this year, instructs readers how to “survive and prosper during the great deflation of 2014-2019.”

The problem is that the mainstream financial media isn’t designed to help you invest better. Its purpose is to entertain you. And oftentimes that’s accomplished by making things seem simpler and more certain than they really are.

Financial commentator Josh Brown discusses this point

in his latest book, Clash of the Financial Pundits:

Of all the verticals, financial media is the only one where there’s supposed to be some sort of responsibility that comes along with it. Maybe politics a little. But when you think about fashion, art, sports, Hollywood gossip, in all of these different huge categories of news — by the way, most of those dwarf financial news — there is no responsibility.

People don’t watch ESPN and then think they’re supposed to go out and play tackle football with 300-pound guys. But for some reason, when they watch financial or business news, they then take the next step in a lot of cases and say “I’m supposed to act on this now.”

6. Time is your “last remaining edge” on Wall St.

After reading all of this, you’d be excused for throwing your hands in the air and concluding that investing in stocks, and not just trading them, is a fool’s errand. But that would be a mistake.

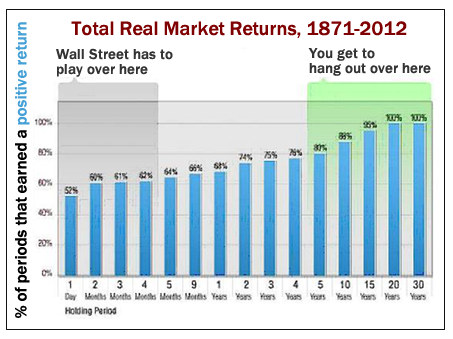

The truth is that genuine investing is a lucrative and worthwhile activity. You just have to do it the right way by taking advantage of what my colleague Morgan Housel calls your “last remaining edge on Wall Street.” What Morgan’s referring to is time — that is, your investment horizon.

As he explains:

The biggest risk investors face is losing money between now and whenever they’ll need it (retirement, school, etc.). The good news for you — and bad news for Wall Street — is that the odds of losing money drops precipitously the longer you’re invested for.

To illustrate this point, Morgan drew up the following chart, which is based on the S&P 500’s performance from 1871 to 2012. Based on this analysis, the chance of losing money in the market drops to zero once your holding period reaches 20 years.

The reasons are twofold. In the first case, long holding periods smooth out short-term irrational fluctuations in the market. That allows stocks as a whole to mimic the irrepressible climb of U.S. gross domestic product. And in the second case, a longer holding period exposes your portfolio to the law of compounding returns.

It’s for these reasons that Buffett wrote in his 1988 letter to shareholders that “when we own portions of outstanding businesses with outstanding managements, our favorite holding period is forever.”

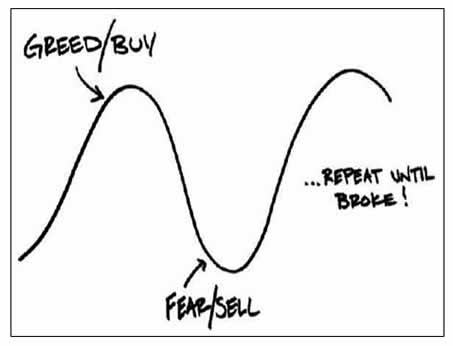

7. Our biggest challenge is to suppress or instincts.

This may seem like a dispiriting way to end a list about how to invest, but recognizing that the vast majority of us are biologically designed to fail is critical if we want to avoid doing so. The problem is that we make investing decisions based on how we feel rather than on what we know.

When we feel as if things are going great, we get greedy and pour money into the market. Then, when things take a turn for the worse, fear incites us to sell out. It’s the classic case of buying high and selling low.

Here’s how Carl Richards sums it up with a Sharpie:

IMPORTANT: This website is only intended for clients and interested investors residing in states in which the Adviser is qualified to provide investment advisory services, and is not an invitation to invest. Please contact us to find out if we are qualified to provide investment advisory services in the state where you reside and to learn more about what we do.

THIS INFORMATION IS BELIEVED BY US TO BE ACCURATE BUT MAY CONTAIN ERRORS. IT IS GENERIC AND MAY NOT BE SUITABLE TO YOUR PARTICULAR SITUATION. DO NOT RELY ON IT. NEVER INVEST WITHOUT CAREFULLY REVIEWING OFFERING DOCUMENTS, ON WHICH ALONE YOU SHOULD RELY. ALL INVESTING ENTAILS RISK. CAPITAL NOT GUARANTEED.